ZOI PAPPA has achieved what many young Greek artists are striving for these days: the growing appreciation and successful exhibiting of her work abroad. She just found out that she will be participating in the Arte Art Prize Laguna, taking place at the Arsenale of Venice (March 25 to April 9), about a month before the 57th Venice Biennale kicks off. A good time to be in Venice! Pappa’s Duchampian spirit also led her last year to be selected for the show ‘Bicycle Wheels – Homage to Duchamp’, in Italy’s Ortigia. Furthermore, this artist (whose work also features in the ‘Saatchi art’ online gallery), is a winner of international art prizes, a curator of controversial shows, and an artist with a dual identity. She is also an art teacher, and a mum. In recent years, Pappa has managed to spread her wings and to exhibit her works in exciting shows and projects in London and Italy. Her work is both in-your-face and romantic: ranging from masks of meat to interventions on the niceties of domestic flowery wallpaper. Pappa’s tongue-in-cheek or even macabre humour can be both subtle and acidic; A reflection of the chameleon-like nature of contemporary reality and its sugar-coated yet satirical, cut-throat world… full of unexpected surprises. We met through linkedin initially, and kicked off a long written discussion about her work and other matters, through various social media, which has now turned into a creative dialogue/interview of sorts. You can read it here, but due to its length, whoever gets to the end, wins a gold medal!

S.S. I have an idea – if you are interested, let’s talk a bit via emails/fb, that way when we meet, we will already know each other in a sense. These are the wonders of the internet. Such freedom.

Z.P. A great tool for ‘vampire mums’…

SS. Who work when their kids sleep!

Z.P. Stella this is a great idea! I would love to do this! But right now I am in my exhibition in London and have to speak with people!

SS. Ok, well let’s start with stuff I want to ask you about your work, so I’m sending you some questions.

Z.P. Ahaha!!! I just read your questions! It is so nice getting to know you, I can sense your personality. You are full of surprises and diversities. They are so honest, clever, funny, passionate, tender to the point of childlike. I adore that element of innocence and deep intelligence. I can easily see your love for art. It makes me feel like l would like to ask you some questions too. I sense that this is going to be a long dialogue! But I look forward to our vampire mum meeting afterwards. Lately, Abramovic was talking badly about mum artists. She was saying that women artists cannot be mums. Well she is wrong! Putting yourself second makes you a more substantial artist. Maternity teaches you sacrifice, unconventional love and giving. It teaches you the importance of life and continuation. True art contains relationships and life.

Z.P. A great tool for ‘vampire mums’…

SS. Who work when their kids sleep!

Z.P. Stella this is a great idea! I would love to do this! But right now I am in my exhibition in London and have to speak with people!

SS. Ok, well let’s start with stuff I want to ask you about your work, so I’m sending you some questions.

Z.P. Ahaha!!! I just read your questions! It is so nice getting to know you, I can sense your personality. You are full of surprises and diversities. They are so honest, clever, funny, passionate, tender to the point of childlike. I adore that element of innocence and deep intelligence. I can easily see your love for art. It makes me feel like l would like to ask you some questions too. I sense that this is going to be a long dialogue! But I look forward to our vampire mum meeting afterwards. Lately, Abramovic was talking badly about mum artists. She was saying that women artists cannot be mums. Well she is wrong! Putting yourself second makes you a more substantial artist. Maternity teaches you sacrifice, unconventional love and giving. It teaches you the importance of life and continuation. True art contains relationships and life.

S.S. Maybe being a mother and an artist is better than being a mother and a businesswoman, for example: you can work from home, it’s a job with flexible hours, which suits a mum, and motherhood is a whole creative experience in itself. For me (as a journalist/art critic), motherhood really affected me – I stayed home for a decade (!!!!). I always tried to be doing something creative though in that time. Journalism is tough on mums too… and doesn’t pay either, especially today.

But let’s start at the beginning: when did you decide or realise, you wanted to be an artist?

Z.P. At the age of two. I did not select art. Art selected me. When I was a little girl, I was unable to speak well, I had a lisp and hardly anyone could understand me. One day, I wanted to eat a pomegranate but nobody could figure out what I was trying to say, so I took a pencil and drew it. Before I managed to talk, I was able to draw. From my early years, art became a necessity, a means of communication with the others.

S.S. In Greece, it’s the kind of profession that parents dread their kids to choose. Did you have support or not from your family?

Z.P. Not at all! Being an artist is not a profession for the majority of Greek parents. In fact an artist is often considered to be the ‘crazy person’ of the village… My mum knew that I was different. She used to hide or throw away all of my drawings, she did not want to encourage me to follow this path. As a kid we would go with my sister to the art school founded by Dimitris Mytaras in Halkida, which was run by his wife Harikleia (also known as ‘Zouzou’). The space was small and so there was a selection procedure to get accepted. I was selected but my sister wasn’t, but I never learnt about this and we both stopped going to Mytaras.

When I grew up and had to choose my profession, they persuaded me that architecture would be ideal for me. I took the final exams and passed design with the best grade in Greece. I refused to read and pass the other lessons. Then I insisted that all I wanted to be was an artist and I had to fight for it. So for a whole summer, from dawn till dusk, I would take a hat and a fishing rod and go fishing on Halkida’s central shore. My parents started worrying about me and asked me what was wrong. I told them that they could choose my future, but I gave them two options: painter or fisherman? My father became a bit more supportive then.

But let’s start at the beginning: when did you decide or realise, you wanted to be an artist?

Z.P. At the age of two. I did not select art. Art selected me. When I was a little girl, I was unable to speak well, I had a lisp and hardly anyone could understand me. One day, I wanted to eat a pomegranate but nobody could figure out what I was trying to say, so I took a pencil and drew it. Before I managed to talk, I was able to draw. From my early years, art became a necessity, a means of communication with the others.

S.S. In Greece, it’s the kind of profession that parents dread their kids to choose. Did you have support or not from your family?

Z.P. Not at all! Being an artist is not a profession for the majority of Greek parents. In fact an artist is often considered to be the ‘crazy person’ of the village… My mum knew that I was different. She used to hide or throw away all of my drawings, she did not want to encourage me to follow this path. As a kid we would go with my sister to the art school founded by Dimitris Mytaras in Halkida, which was run by his wife Harikleia (also known as ‘Zouzou’). The space was small and so there was a selection procedure to get accepted. I was selected but my sister wasn’t, but I never learnt about this and we both stopped going to Mytaras.

When I grew up and had to choose my profession, they persuaded me that architecture would be ideal for me. I took the final exams and passed design with the best grade in Greece. I refused to read and pass the other lessons. Then I insisted that all I wanted to be was an artist and I had to fight for it. So for a whole summer, from dawn till dusk, I would take a hat and a fishing rod and go fishing on Halkida’s central shore. My parents started worrying about me and asked me what was wrong. I told them that they could choose my future, but I gave them two options: painter or fisherman? My father became a bit more supportive then.

S.S. I love the photo with you and your father, where in one hand he’s holding a large fish, and in the other he’s holding you (upside down)!

You live in Halkida, what’s the art scene like there?

Z.P.There is no such thing in Halkida or in most Greek provinces. There are no galleries, only commercial art shops selling frames. But I believe that we should and could build one.

S.S. You studied art at the Visual and Applied Arts Department of Thessaloniki’s Aristotle University, then went on to the Glasgow School of Art for an M.F.A. How do these two art schools compare? What do you feel you gained from them, or didn’t?

Z.P. In Thessaloniki I learnt to walk. During my first years there I had Dimitreas as my tutor. Dimitreas had a different approach to females, he thought that we were not able to be good artists because we give up art for a family. So, I felt pushed aside. Then a new tutor Yiannis Fokas came to the school. I became one of his best students. Fokas was very passionate and open-minded. He inspired me and made me start reading, visiting and participating in exhibitions. He literally opened my eyes, he was very supportive. He taught me how to be an artist.

On the other hand the M.F.A. at the Glasgow School of Art played a vital role in my life. The very first words that I heard there were: “O.K., you are a good painter, so what?” I faced a hostile, judgmental and tough environment and I had to survive. I stopped painting in order to rethink my art. I experimented with other mediums, photography, video and performance. I learnt to research, to defend my art and to be critical. A very basic thing that I Iearned from G.S.A. was the philosophy of D.I.Y. (Do it yourself).

S.S. You are both an artist and curator – that’s quite unusual. How do you manage to combine these two ‘identities’? Some would say that they are very different (creative vs organisation/management), while there is of course common ground too (the art).

Z.P. They are not so different. Being an artist and curator have the same starting points: a strong project and good research. As an artist you have to curate and promote your work, as an artist/curator you do the same for the participants and you are also in charge of constructing the visual and non-visual dialogue between the artworks. Then, you have to construct a dialogue between the audience and the artworks, in order to present society with something substantial and coherent.

S.S. Why did you decide to become both?

Z.P. Because I was never part of any network. I also had a lot of things to say. I had to acquire a voice. I had to do it myself, on my own.

You live in Halkida, what’s the art scene like there?

Z.P.There is no such thing in Halkida or in most Greek provinces. There are no galleries, only commercial art shops selling frames. But I believe that we should and could build one.

S.S. You studied art at the Visual and Applied Arts Department of Thessaloniki’s Aristotle University, then went on to the Glasgow School of Art for an M.F.A. How do these two art schools compare? What do you feel you gained from them, or didn’t?

Z.P. In Thessaloniki I learnt to walk. During my first years there I had Dimitreas as my tutor. Dimitreas had a different approach to females, he thought that we were not able to be good artists because we give up art for a family. So, I felt pushed aside. Then a new tutor Yiannis Fokas came to the school. I became one of his best students. Fokas was very passionate and open-minded. He inspired me and made me start reading, visiting and participating in exhibitions. He literally opened my eyes, he was very supportive. He taught me how to be an artist.

On the other hand the M.F.A. at the Glasgow School of Art played a vital role in my life. The very first words that I heard there were: “O.K., you are a good painter, so what?” I faced a hostile, judgmental and tough environment and I had to survive. I stopped painting in order to rethink my art. I experimented with other mediums, photography, video and performance. I learnt to research, to defend my art and to be critical. A very basic thing that I Iearned from G.S.A. was the philosophy of D.I.Y. (Do it yourself).

S.S. You are both an artist and curator – that’s quite unusual. How do you manage to combine these two ‘identities’? Some would say that they are very different (creative vs organisation/management), while there is of course common ground too (the art).

Z.P. They are not so different. Being an artist and curator have the same starting points: a strong project and good research. As an artist you have to curate and promote your work, as an artist/curator you do the same for the participants and you are also in charge of constructing the visual and non-visual dialogue between the artworks. Then, you have to construct a dialogue between the audience and the artworks, in order to present society with something substantial and coherent.

S.S. Why did you decide to become both?

Z.P. Because I was never part of any network. I also had a lot of things to say. I had to acquire a voice. I had to do it myself, on my own.

S.S. An artist-turned-politician once said to me that the Greek art world is ‘venomous’. It made me wonder though, how can it be more venomous than Greek politics? You have preferred to have a more independent career as an artist, what are the pluses and minuses?

Z.P. The world of art is full of businessmen artists and businessmen curators that take themselves too seriously and exclude other people. Art is not about that. Those people have gained serious positions in the art world but in my opinion they lose out in terms of human relationships. They do not want to share a piece of their pie and when they see someone that they feel is dangerous, they try to intimidate them. I do not see any minuses in being independent. Selling art is important in order to survive but it was never my priority for making art.

If you are independent, you don’t compromise with the established world of art or belong to a network. You need to become innocent and romantic in order to have a genuine commitment to art. If your purpose is to gain something e.g. recognition, money, power, then you are not involved with art and communication. If I find someone with the same ideas as me, I will collaborate.

For me, the process of making art is tied to an existential need. But I have nothing against the gallery system or earning money out of art. I just have a different philosophy: Throughout my life I have not only worked for free, but l have also invested in art all the money I gained from working as a tutor, or from teaching art. I work so that l can support art. You would be surprised how many good, established artists work for free.

Z.P. The world of art is full of businessmen artists and businessmen curators that take themselves too seriously and exclude other people. Art is not about that. Those people have gained serious positions in the art world but in my opinion they lose out in terms of human relationships. They do not want to share a piece of their pie and when they see someone that they feel is dangerous, they try to intimidate them. I do not see any minuses in being independent. Selling art is important in order to survive but it was never my priority for making art.

If you are independent, you don’t compromise with the established world of art or belong to a network. You need to become innocent and romantic in order to have a genuine commitment to art. If your purpose is to gain something e.g. recognition, money, power, then you are not involved with art and communication. If I find someone with the same ideas as me, I will collaborate.

For me, the process of making art is tied to an existential need. But I have nothing against the gallery system or earning money out of art. I just have a different philosophy: Throughout my life I have not only worked for free, but l have also invested in art all the money I gained from working as a tutor, or from teaching art. I work so that l can support art. You would be surprised how many good, established artists work for free.

S.S. And many journalists/art critics too! But yes, let’s talk about this philosophy – making money to make art, rather than making art to make money. That kind of breaks the direct link between art and money. And sets art ‘free’ in a sense. The show ‘Trauma Queen’ that you curated with Harris Kondosphyris in 2007 was also created without sponsorship or funds, but instead with a kind of ‘fair trade’ system. That’s interesting, but how is it possible? Just with each person volunteering to put in the work? That can be effective only to a certain degree. How many artists would accept to work for free? ‘Trauma Queen’ was also pretty radical and got mixed reviews.

Z.P. ‘Trauma Queen’ took place in an abandoned hotel in Omonoia Square without any budget. It was the year that for the first time, we had 2 Biennales in Greece: The 1st Athens Biennale, entitled “Destroy Athens” and the 1st Thessaloniki Biennale, organised by the State Museum of Contemporary Art. Another project that ran parallel to the 1st Athens Biennale was the 1st Remap. Remap tried to offer an additional spectrum to the conceptual & methodological context of ‘Destroy Athens’ by engaging with a particular area of Athens and redefining the inhabitation and utilisation of different sites. Remap was presented in different settings, fully functional ones as well as derelict buildings, lots and public spaces, around several blocks of the Kerameikos area.

S.S. Hmm… We are about to witness an even bigger artistic ‘boom’ in Athens starting this spring, with the upcoming Documenta 14, the resurrection of Remap, a revamped art athina (with a new General Director, Yorgos Taxiarchopoulos), plus the two biennales you mentioned, plus the grand official opening of EMST later in October (not to mention the summer shows on the islands, e.g. Andros, Hydra). I don’t think the cultural tourists will want to leave this year!

Z.P. ‘Trauma Queen’ took place in an abandoned hotel in Omonoia Square without any budget. It was the year that for the first time, we had 2 Biennales in Greece: The 1st Athens Biennale, entitled “Destroy Athens” and the 1st Thessaloniki Biennale, organised by the State Museum of Contemporary Art. Another project that ran parallel to the 1st Athens Biennale was the 1st Remap. Remap tried to offer an additional spectrum to the conceptual & methodological context of ‘Destroy Athens’ by engaging with a particular area of Athens and redefining the inhabitation and utilisation of different sites. Remap was presented in different settings, fully functional ones as well as derelict buildings, lots and public spaces, around several blocks of the Kerameikos area.

S.S. Hmm… We are about to witness an even bigger artistic ‘boom’ in Athens starting this spring, with the upcoming Documenta 14, the resurrection of Remap, a revamped art athina (with a new General Director, Yorgos Taxiarchopoulos), plus the two biennales you mentioned, plus the grand official opening of EMST later in October (not to mention the summer shows on the islands, e.g. Andros, Hydra). I don’t think the cultural tourists will want to leave this year!

Z.P. Well 2007 was also a period of remarkable change in terms of Greece’s artistic matters. So it was within a similar kind of framework, that we decided to contribute and get involved with our current situation, and to examine ways in which we could redefine aims regarding Greek art. So we decided to organise the contemporary art exhibition ‘Trauma Queen’. ‘Trauma Queen’ traced various kinds of social disability taking form through art, as possible manifestations of a pathogenic present condition which can lead to real disability. 26 artists from different cultural backgrounds exhibited their work. The artists used a wide range of mediums of expression.

Given the difficulty of funding for independent art productions, ‘Trauma Queen’ adopted a ‘fair-trade’ policy. We made an attempt at introducing to Greece the notion of fair-trade collaboration among all participating artists; within a framework of close cooperation and exchange, we wanted to enhance intercultural contact and trust, promoting new independent forms of organization for art events. As a consequence, invited artists were responsible for their journey’s expenses and the transportation of their work. In the ‘Trauma Queen’ exhibition “egos” undergo dispersion and expansion. ‘I’ becomes ‘we’. It was also strictly a non-profit event.

S.S. How would you describe the gallery scene in Greece?

Z.P. Most of the galleries try to be contemporary, and promote ‘aesthetics’ and ‘fashion’. Others promote “intelligence” and “political correctness”. But this is a general illness of the contemporary art world that feeds exclusion to its non-members. Hopefully there are also some serious spaces and people that have the knowledge and are devoted to presenting true creation.

Given the difficulty of funding for independent art productions, ‘Trauma Queen’ adopted a ‘fair-trade’ policy. We made an attempt at introducing to Greece the notion of fair-trade collaboration among all participating artists; within a framework of close cooperation and exchange, we wanted to enhance intercultural contact and trust, promoting new independent forms of organization for art events. As a consequence, invited artists were responsible for their journey’s expenses and the transportation of their work. In the ‘Trauma Queen’ exhibition “egos” undergo dispersion and expansion. ‘I’ becomes ‘we’. It was also strictly a non-profit event.

S.S. How would you describe the gallery scene in Greece?

Z.P. Most of the galleries try to be contemporary, and promote ‘aesthetics’ and ‘fashion’. Others promote “intelligence” and “political correctness”. But this is a general illness of the contemporary art world that feeds exclusion to its non-members. Hopefully there are also some serious spaces and people that have the knowledge and are devoted to presenting true creation.

S.S. You are also a double persona in terms of your art: Your performance art is cutting-edge and provocative (making masks out of all sorts of things – from a fish, or meat). You even cut off your own hair and stuck it on your face, making a mask out of it. But your paintings are dreamlike, romantic even – but with twist (if you study them closer). Tell us about both.

Z.P. For me, it’s all the same. The only things that change are the medium and the first impression. My performances have a more obvious impact on the viewer, are more communicative and use strong visual imagery that causes a reaction. But this is only the first impression. My transformation vents feelings of shame and alienation in parallel with senses of relief, free will, rebellion, and power. All these are common human sentiments that when you recognize them, and get over the initial shock, you then feel familiar and compassionate towards the persona. My paintings also present a diversity of feelings via a diversity of images and symbols. My paintings give a soft first impression but when you look closer, they are the opposite of what they seem. My performances deal with the transformation of matter just like my paintings do. It is a different approach. And they both use ready-made materials. The core of my concept is the idea of experimenting with the processes of perception. Nothing is as it seems, nothing is taken for granted. My art presents transient worlds, where subjects, objects and territories live in states of continuous transformation. They have surprising potential for renaissance, creation, evolution, dissolution and disappearance.

Z.P. For me, it’s all the same. The only things that change are the medium and the first impression. My performances have a more obvious impact on the viewer, are more communicative and use strong visual imagery that causes a reaction. But this is only the first impression. My transformation vents feelings of shame and alienation in parallel with senses of relief, free will, rebellion, and power. All these are common human sentiments that when you recognize them, and get over the initial shock, you then feel familiar and compassionate towards the persona. My paintings also present a diversity of feelings via a diversity of images and symbols. My paintings give a soft first impression but when you look closer, they are the opposite of what they seem. My performances deal with the transformation of matter just like my paintings do. It is a different approach. And they both use ready-made materials. The core of my concept is the idea of experimenting with the processes of perception. Nothing is as it seems, nothing is taken for granted. My art presents transient worlds, where subjects, objects and territories live in states of continuous transformation. They have surprising potential for renaissance, creation, evolution, dissolution and disappearance.

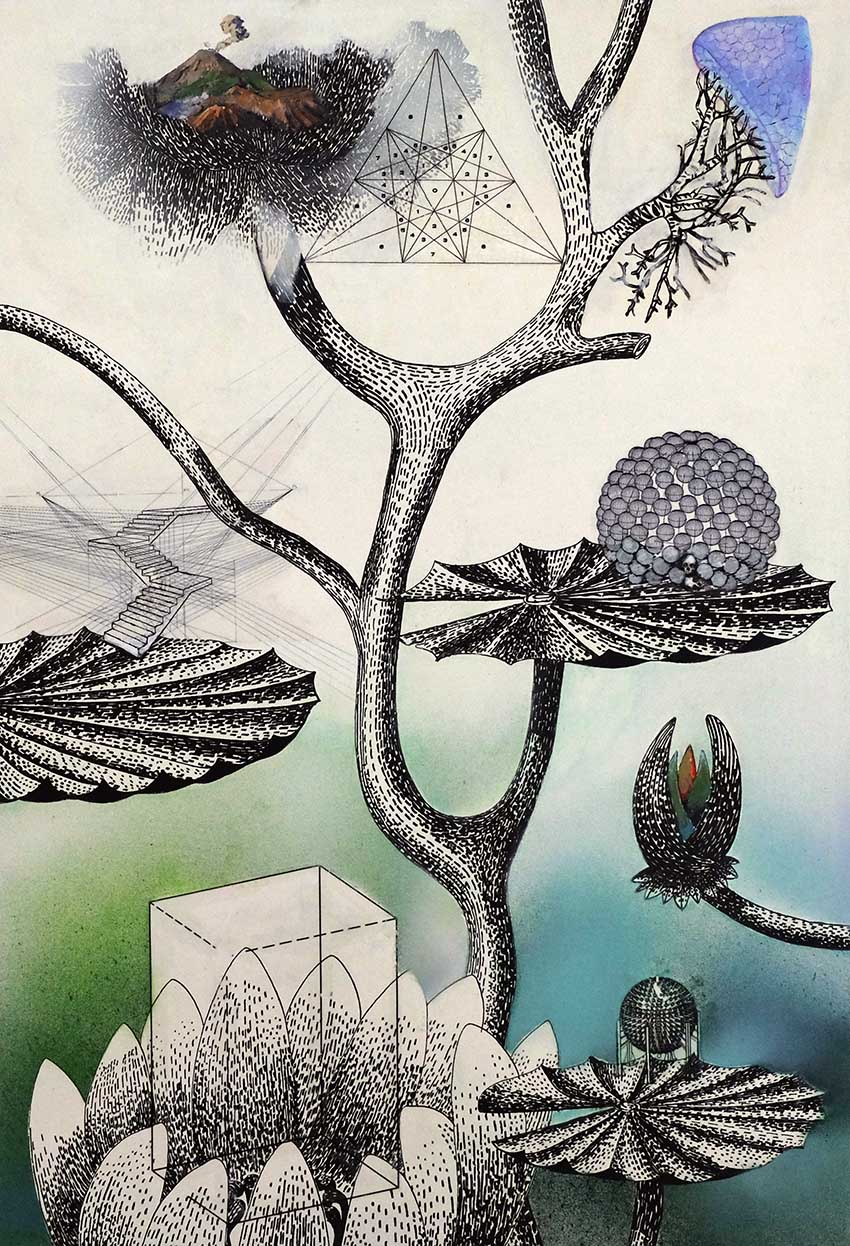

S.S. Personally, I love the way your paintings combine flower motifs with others taken from a whole host of other sources, such as science. They take me back to my childhood in London, and to some very bold flowery wallpaper in one very small room. The flowers also looked like sad and happy faces! How did this concept develop?

Z.P. During my M.F.A. I lived in Glasgow for three years. Wallpaper is a domestic material that is commonly used in U.K. houses. I used to look at these wallpapers and imagine bizarre things growing out of the tapestry florals. When I returned from Scotland I found a big book of wallpaper samples in the garbage. I had just returned to Greece and I had no studio to work in, so I started painting over them. After several experiments, in 2007, I made the first of my ‘garden’ works – entitled ‘Life Garden’. It shows a burning landscape with its reflection in the water depicting a dreamy, ideal, green condition of the same landscape. Little animals pop up from inside the flowers as well as anatomical and biological forms (like a skeleton, a tongue, an ovary). Then several years passed during which I didn’t paint anything, but I never stopped my research. Between 2007-2009 I dealt with my masks. When I was 8 months pregnant I did my last performance ‘Up Against The Wall Motherfuckers’. In 2009 I gave birth to my daughter Eleni. The creation of life left me artistically empty. I had nothing to say for a while. My priority was the autonomy of little Eleni.

S.S. When did you feel ready to return to art?

Z.P. In 2014 I got back in action: I saw an invitation for ICRI, Research and Art – a Contemporary Art Exhibition that was presented as part of the Megaron Plus programme in Athens. I made a site-specific work – the ‘Science Garden’, where all sorts of science starts to flourish from my wallpaper patterns: nanotechnology, physics, mathematics, architecture, chemistry, biology and anatomy. I discovered my passion for mathematics and human achievements.

S.S. You have also said that ‘My desire is to go beyond current morality’. Sounds scary, can you explain?

Z.P. Yes, I believe that current morality and prevailing values put barriers on human existence and creativity and cause exclusion, guilt and misery. We need to get over morality and return to innocence in order to create a world with substance and freedom.

Z.P. During my M.F.A. I lived in Glasgow for three years. Wallpaper is a domestic material that is commonly used in U.K. houses. I used to look at these wallpapers and imagine bizarre things growing out of the tapestry florals. When I returned from Scotland I found a big book of wallpaper samples in the garbage. I had just returned to Greece and I had no studio to work in, so I started painting over them. After several experiments, in 2007, I made the first of my ‘garden’ works – entitled ‘Life Garden’. It shows a burning landscape with its reflection in the water depicting a dreamy, ideal, green condition of the same landscape. Little animals pop up from inside the flowers as well as anatomical and biological forms (like a skeleton, a tongue, an ovary). Then several years passed during which I didn’t paint anything, but I never stopped my research. Between 2007-2009 I dealt with my masks. When I was 8 months pregnant I did my last performance ‘Up Against The Wall Motherfuckers’. In 2009 I gave birth to my daughter Eleni. The creation of life left me artistically empty. I had nothing to say for a while. My priority was the autonomy of little Eleni.

S.S. When did you feel ready to return to art?

Z.P. In 2014 I got back in action: I saw an invitation for ICRI, Research and Art – a Contemporary Art Exhibition that was presented as part of the Megaron Plus programme in Athens. I made a site-specific work – the ‘Science Garden’, where all sorts of science starts to flourish from my wallpaper patterns: nanotechnology, physics, mathematics, architecture, chemistry, biology and anatomy. I discovered my passion for mathematics and human achievements.

S.S. You have also said that ‘My desire is to go beyond current morality’. Sounds scary, can you explain?

Z.P. Yes, I believe that current morality and prevailing values put barriers on human existence and creativity and cause exclusion, guilt and misery. We need to get over morality and return to innocence in order to create a world with substance and freedom.

S.S. Back in 2006, you curated and took part in the show ‘Who cares about Greek art?’, which took place at your own space, called Zoi’s. Tell us about this show, your art space and PLEASE tell us who DOES care about Greek art today?

Z.P. Obviously we both do! That was the first show that I curated without a budget. In Greece I had never cared about or questioned my Greek identity and I avoided anything that had to do with this issue, or anything Greek. I did not want the Greek label. I considered myself a universal person, without national identity. I only sensed my Greekness when I left Greece, and went abroad. I curated ‘Who cares about Greek art’, just after I returned from my studies at the Glasgow School of Art.

After 3 years away from my country and having been exposed to a different culture, I was trying to adjust myself to the Greek reality, to evaluate my experience in the U.K. and understand to what extent I had been influenced. I was wondering what had left and what had stayed and also, who cares about Greek art, who cares if it is Greek, who cares if it is art?

All the participants were alumni of U.K. universities who had studied art. They had to be present and also pay for their round trip. Zoi’s was the venue where the event was held. It was my underground studio in Thision that had been used to present the work of other artists too. The event attracted a big audience and gained a lot of publicity. We also published a catalogue.

Z.P. Obviously we both do! That was the first show that I curated without a budget. In Greece I had never cared about or questioned my Greek identity and I avoided anything that had to do with this issue, or anything Greek. I did not want the Greek label. I considered myself a universal person, without national identity. I only sensed my Greekness when I left Greece, and went abroad. I curated ‘Who cares about Greek art’, just after I returned from my studies at the Glasgow School of Art.

After 3 years away from my country and having been exposed to a different culture, I was trying to adjust myself to the Greek reality, to evaluate my experience in the U.K. and understand to what extent I had been influenced. I was wondering what had left and what had stayed and also, who cares about Greek art, who cares if it is Greek, who cares if it is art?

All the participants were alumni of U.K. universities who had studied art. They had to be present and also pay for their round trip. Zoi’s was the venue where the event was held. It was my underground studio in Thision that had been used to present the work of other artists too. The event attracted a big audience and gained a lot of publicity. We also published a catalogue.

S.S. You were recently in London, for the show Art Rooms 2017 (January 21-3), at the Melia White House on Albany St. This prestigious event via which 70 artists out of around 800 applicants are selected, is designed to showcase independent artists from around the world. How did you find this experience?

Z.P. To tell you the truth I was a bit shocked. It was the first time I participated in something so commercial but I guess that’s the whole point of an art fair. As an independent artist I used to participate in more alternative venues. The art fair was very well organised and publicized and it was very big and crowded. Each artist had his/her own room and was responsible to open and close it. That was the most interesting part because artists had the chance to communicate with the audience.

It was separated into 4 sections: U.K, Europe, Canada-America, Middle and Far East.

The director Cristina Cellini Antonini and the curatorial board were very professional and supportive to the artists.

Z.P. To tell you the truth I was a bit shocked. It was the first time I participated in something so commercial but I guess that’s the whole point of an art fair. As an independent artist I used to participate in more alternative venues. The art fair was very well organised and publicized and it was very big and crowded. Each artist had his/her own room and was responsible to open and close it. That was the most interesting part because artists had the chance to communicate with the audience.

It was separated into 4 sections: U.K, Europe, Canada-America, Middle and Far East.

The director Cristina Cellini Antonini and the curatorial board were very professional and supportive to the artists.

S.S. All the more Greek artists today, with the crisis, have been trying to exhibit abroad. How was this experience for you?

Z.P. For me it is easier to exhibit internationally rather than in Greece. Only my art matters and I want to be judged for this and not for my public profile. In Greece, in order to belong in the contemporary art scene you must be at every opening and have social abilities. But the most important artists in the history of art were antisocial and were excluded from the system.

Z.P. For me it is easier to exhibit internationally rather than in Greece. Only my art matters and I want to be judged for this and not for my public profile. In Greece, in order to belong in the contemporary art scene you must be at every opening and have social abilities. But the most important artists in the history of art were antisocial and were excluded from the system.

S.S. Michelangelo was antisocial, but this didn’t stop him from getting commissions, or from becoming famous, even during his own lifetime. But there are many different kinds of artists. Our age has certainly seen to the rise of the ‘businessman artist’, but then there have always been examples of these artists in history too (who were also very talented). Maybe it was Warhol who paved the way for today’s businessmen artists. But I can understand how an artist today can be in the mindset of “Why shouldn’t I make money, while I’m alive, rather than someone making money out of me when I’m dead?”.

There have been of course so many talented artists that were not ‘part of the system’, or who were doing their own thing, that never got promoted or recognized. Some got recognition later, (as is the case for many female artists in history), while others didn’t (e.g. there are hardly any Greek artists in the major European history of art books). Money (or politics) can be a motive for the person who decides to promote them later. But money and art have a very interesting relationship. Art without money is like a ‘bride stripped bare by her bachelors’ (ha ha!), sorry, I’m getting silly now. But, it’s very noble to not be interested in the money. It makes for a more esoteric, soul-searching, spiritual art practice, art for art’s sake.

I get the impression that the Dada spirit is also very much alive in your artistic/curatorial philosophy! I must admit though, the dead pigeon in the exhibition ‘Trauma Queen’ was rather disturbing. I assume that was the aim though. That pigeon died because its leg had got caught and it couldn’t fly away. It was kind of an apt symbol of the relationship of art and money – that can kill art’s freedom. But, at the end of the day, this image was shocking. So I ask you, what is gained through art that aims to shock?

Z.P. Shocking is always the bare truth that true art and life carry. We found the dead pigeon in the building. Nature became art by accident. Of course I care too about money and it would be great if we could survive doing art. But money is not my priority or my obsession, art is.

By the way, I can’t buy my art, because art is too expensive. It is only for the aristocracy. Unfortunately, it is they and art curators who are deciding what art is worth seeing today.

S.S. Yes, this issue of the price of art is something that I question too. Most people can’t afford art. Art collecting is an aristocrat’s hobby! And that is sad, because in that sense it is not like literature for example. A great book can be bought by everyone. A great film or a great piece of music too is accessible to everyone. Maybe working in multiples is the answer for art to be available to everyone, the same way film and music and literature work. To create a kind of art that works well in multiples. (Because a print of a great painting pales in comparison to the original work.)

But the whole art system is based on collecting unique art ‘objects’ and placing them in a museum or collection – art as an investment. Mind you, I don’t mind the fact that I can’t buy great art, as long as I can go and see it. It’s like going to a concert! The memory and the visual experience stays with you and changes you forever. That’s why art education is very, very important. So that the people who finally are able to buy the ‘expensive’, unique art works, can make the right choices, have a good eye. But more importantly, so that everyone can enjoy art and go to museums etc and understand it.

Back to you though: In 2015 you won 1st prize at Rome’s Nuovi Mondi – Corte competition. Tell us about this event that brings professionals together from around the world and from the entire art spectrum.

There have been of course so many talented artists that were not ‘part of the system’, or who were doing their own thing, that never got promoted or recognized. Some got recognition later, (as is the case for many female artists in history), while others didn’t (e.g. there are hardly any Greek artists in the major European history of art books). Money (or politics) can be a motive for the person who decides to promote them later. But money and art have a very interesting relationship. Art without money is like a ‘bride stripped bare by her bachelors’ (ha ha!), sorry, I’m getting silly now. But, it’s very noble to not be interested in the money. It makes for a more esoteric, soul-searching, spiritual art practice, art for art’s sake.

I get the impression that the Dada spirit is also very much alive in your artistic/curatorial philosophy! I must admit though, the dead pigeon in the exhibition ‘Trauma Queen’ was rather disturbing. I assume that was the aim though. That pigeon died because its leg had got caught and it couldn’t fly away. It was kind of an apt symbol of the relationship of art and money – that can kill art’s freedom. But, at the end of the day, this image was shocking. So I ask you, what is gained through art that aims to shock?

Z.P. Shocking is always the bare truth that true art and life carry. We found the dead pigeon in the building. Nature became art by accident. Of course I care too about money and it would be great if we could survive doing art. But money is not my priority or my obsession, art is.

By the way, I can’t buy my art, because art is too expensive. It is only for the aristocracy. Unfortunately, it is they and art curators who are deciding what art is worth seeing today.

S.S. Yes, this issue of the price of art is something that I question too. Most people can’t afford art. Art collecting is an aristocrat’s hobby! And that is sad, because in that sense it is not like literature for example. A great book can be bought by everyone. A great film or a great piece of music too is accessible to everyone. Maybe working in multiples is the answer for art to be available to everyone, the same way film and music and literature work. To create a kind of art that works well in multiples. (Because a print of a great painting pales in comparison to the original work.)

But the whole art system is based on collecting unique art ‘objects’ and placing them in a museum or collection – art as an investment. Mind you, I don’t mind the fact that I can’t buy great art, as long as I can go and see it. It’s like going to a concert! The memory and the visual experience stays with you and changes you forever. That’s why art education is very, very important. So that the people who finally are able to buy the ‘expensive’, unique art works, can make the right choices, have a good eye. But more importantly, so that everyone can enjoy art and go to museums etc and understand it.

Back to you though: In 2015 you won 1st prize at Rome’s Nuovi Mondi – Corte competition. Tell us about this event that brings professionals together from around the world and from the entire art spectrum.

Z.P. Corte is an extended family of experts in different fields that weave their working lives within the same high walls. Founded in Rome in September of 2013, it has already won a place in the increasingly interconnected middle ground that embraces architecture, design, communication, visual arts and cultural services. ‘Nuovi Mondi’ was an international contest attended by artists of different nationalities coming from different creative fields. The ‘Nuovi Mondi Creative Contest’ had 112 participants, from 13 countries and 14 creative fields. Eight jurors decided the 10 finalists. The prize for the 10 finalists was a group show in Corte and the publishing of a catalogue. The first winner’s prize was a solo show. We were asked to express our perceptions and interpretations of ‘New Worlds’, meant as new visions, new landscapes, new interpretations and new materials. It was so exciting to be the first winner. In 2015 I had my solo show ‘Gardens in Corte’. With Corte we shared the same concerns, we had synergy and we became friends in the end.

S.S. How about ‘Transleat me’? The 2008 show which you curated and also did a performance for, in which you covered your face with meat – which focused on the power of the translator to distort meaning.

Z.P. ‘Transleat me’ was part of ‘Platform Translation’ – a travelling project involving artists from South America, Europe, and the Middle East. Its main purpose was to explore the concept of translation through artistic practices and critical discourse. The project included exhibitions in five cities: Athens (November, 2008), Santiago de Chile (May, 2009), and Rome, Beirut, and Berlin.

In every country a local curator was invited to develop a reading of the concept from the point of view of his/her particular cultural context; he/she took on the responsibility to invite local artists to participate in the show.

I was the curator of ‘Transleat me’, the exhibition of ‘Platform Translation’ in Athens. It took place on two floors of some abandoned offices on Aiolou Street that Mr. Dragonas had kindly offered to us. Once again, I would like to mention that everything was done with zero money and a lot of joy and team work. I was also the guest curator of ‘Street Hacker’, the exhibition of ‘Platform Translation’ in Santiago, Chile. This is where I did the performance in which I covered my face with meat, for the photographic installation ‘Up Against The Wall Motherfuckers’. It was a protest against dominant power structures. By creating a mysterious anarchist persona by wearing the ‘meat’ masks, I attempted to reinvent myself in order to create a new self out of the conventions of society. Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers was an anarchist affinity group based in New York City. This “street gang with analysis” was famous for its Lower East Side direct action and is said to have inspired members of the Weather Underground and the Yippies. Their name came from a poem by Amiri Baraka. Abbie Hoffman (an American political and social activist and anarchist of the ‘60s) characterized them as “the middle-class nightmare… an anti-media phenomenon simply because their name could not be printed in the social media.”

S.S. How about ‘Transleat me’? The 2008 show which you curated and also did a performance for, in which you covered your face with meat – which focused on the power of the translator to distort meaning.

Z.P. ‘Transleat me’ was part of ‘Platform Translation’ – a travelling project involving artists from South America, Europe, and the Middle East. Its main purpose was to explore the concept of translation through artistic practices and critical discourse. The project included exhibitions in five cities: Athens (November, 2008), Santiago de Chile (May, 2009), and Rome, Beirut, and Berlin.

In every country a local curator was invited to develop a reading of the concept from the point of view of his/her particular cultural context; he/she took on the responsibility to invite local artists to participate in the show.

I was the curator of ‘Transleat me’, the exhibition of ‘Platform Translation’ in Athens. It took place on two floors of some abandoned offices on Aiolou Street that Mr. Dragonas had kindly offered to us. Once again, I would like to mention that everything was done with zero money and a lot of joy and team work. I was also the guest curator of ‘Street Hacker’, the exhibition of ‘Platform Translation’ in Santiago, Chile. This is where I did the performance in which I covered my face with meat, for the photographic installation ‘Up Against The Wall Motherfuckers’. It was a protest against dominant power structures. By creating a mysterious anarchist persona by wearing the ‘meat’ masks, I attempted to reinvent myself in order to create a new self out of the conventions of society. Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers was an anarchist affinity group based in New York City. This “street gang with analysis” was famous for its Lower East Side direct action and is said to have inspired members of the Weather Underground and the Yippies. Their name came from a poem by Amiri Baraka. Abbie Hoffman (an American political and social activist and anarchist of the ‘60s) characterized them as “the middle-class nightmare… an anti-media phenomenon simply because their name could not be printed in the social media.”

S.S. Your work is also on the Saatchi art online gallery

Z.P. Yes, one of the curators of Saatchi, Rebbeca Wilson had contacted me and showed interest in my artwork and I became a featured artist.

S.S. England, Italy, Greece – three very different art scenes which you have experienced. What’s your view on them?

Z.P. In Greece we have a very young and up-to-date audience that cares very much for everything contemporary, while in England we have art lovers of every age. It is amazing how many old English people you can meet daily in Tate modern and in the museums. In Italy there is culture. A deep inherent understanding and love for art that probably derives from its past.

S.S. And what about the future? You have another show in Rome coming up I believe.

Z.P. Yes I will go back to Rome. Now we are discussing the dates. I was selected by the curators Rezarta Zaloshnja and Lori Adragna for a solo show in Canova 22 as winner of the T.I.N.A. Prize (An international prize for a solo exhibition at great contemporary galleries around the globe). Canova 22 was the oven of the famous Italian sculptor Antonio Canova and is located in the heart of Rome next to the Academia of Fine Arts. It is a very historical, alchemical, peculiar and important space.

S.S. You know the question ‘If you were stranded on a desert island, which record would you want to have with you? (assuming there’s a record-player).’ Well, I ask you, which art work would you choose to have with you? (not one of your own!).

Z.P. I am afraid I cannot answer this. Artwork is an idea, a feeling, a knowledge that I experienced and I will always carry with me, not an object. As you already said ‘The memory and the visual experience stays with you and changes you forever.’

• Please post a comment, if you would like to add to this conversation. The comments will then be incorporated into the dialogue, in order to transform it into an art project of sorts.

Z.P. Yes, one of the curators of Saatchi, Rebbeca Wilson had contacted me and showed interest in my artwork and I became a featured artist.

S.S. England, Italy, Greece – three very different art scenes which you have experienced. What’s your view on them?

Z.P. In Greece we have a very young and up-to-date audience that cares very much for everything contemporary, while in England we have art lovers of every age. It is amazing how many old English people you can meet daily in Tate modern and in the museums. In Italy there is culture. A deep inherent understanding and love for art that probably derives from its past.

S.S. And what about the future? You have another show in Rome coming up I believe.

Z.P. Yes I will go back to Rome. Now we are discussing the dates. I was selected by the curators Rezarta Zaloshnja and Lori Adragna for a solo show in Canova 22 as winner of the T.I.N.A. Prize (An international prize for a solo exhibition at great contemporary galleries around the globe). Canova 22 was the oven of the famous Italian sculptor Antonio Canova and is located in the heart of Rome next to the Academia of Fine Arts. It is a very historical, alchemical, peculiar and important space.

S.S. You know the question ‘If you were stranded on a desert island, which record would you want to have with you? (assuming there’s a record-player).’ Well, I ask you, which art work would you choose to have with you? (not one of your own!).

Z.P. I am afraid I cannot answer this. Artwork is an idea, a feeling, a knowledge that I experienced and I will always carry with me, not an object. As you already said ‘The memory and the visual experience stays with you and changes you forever.’

• Please post a comment, if you would like to add to this conversation. The comments will then be incorporated into the dialogue, in order to transform it into an art project of sorts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed